There is a tradesmen's entrance to the Saatchis' Belgravia home. What comes in through there - Charles's acquisitions, Nigella's white truffles? Is a journalist a tradesman? I'm not sure, so I trot up the stairs to the intimidating main entrance and ring the bell. A young assistant opens the door, and whisks me through the hall. In a blur, I see Magritte's signature beneath a moonlit scene (Was it a bungalow? Did Magritte do bungalows?). Opposite, there is a naked old retainer sitting on a bench who, when I look back down from the stairs, turns out to be Duane Hanson's Man on a Bench.

On the landing, there is a huge framed photograph of Nigella looking quite the pip. But there's no time to study the picture properly because her husband is already shaking my hand and offering me some chilled, cloudy lemonade. "It's from Waitrose," he says, confidingly. "I can really recommend it."

We move to a vast room and sit behind a huge desk before an outsized computer. It's hard not to feel insignificant. Even Saatchi seems an outsized version of himself. He wears a baggy blue, short-sleeved shirt and has eyes that meet yours with sidelong, sad puppyish glances - a premonition of what David Schwimmer will look like at 63.

I have been warned that Charles would prefer it if I didn't write about how messy his house is. I'm quite prepared to adhere to this stricture, chiefly because it isn't. Saatchi disagrees: "It's a toilet here. In the dining room, all there is on the walls is chains where pictures once were, and every morning Nigella says, 'When are you going to put a bloody picture up here?'" Given the size of Saatchi's collection, she has a point. Today, she is nowhere in evidence.

Saatchi is a famously reluctant interviewee. Baghdad-born, Hampstead-raised, one half of the Saatchi & Saatchi ad agency who helped make Thatcher electable, he is generally portrayed as a furtive, latter-day Citizen Kane. The most voracious of contemporary art collectors, he hardly ever makes public appearances and rarely speaks to the press. Asked by readers of the Art Newspaper in 2005 why he doesn't attend even his own openings, he replied: "I don't go to other people's openings, so I extend the same courtesy to my own."

He doesn't give interviews, he says, because "I come over as shifty. One thing that makes my flesh crawl is reading about myself." Nigella, on the other hand, a former journalist, is more comfortable with the press and frequently attends openings on her husband's behalf. "She's very, very charming, very clever, and she's very open so she'll just gab on about anything. With me, as you can see, I'm very shifty and very nervous - that's why I keep my gob shut."

Shifty or not, today Saatchi wants to talk about three things: the website he set up earlier this year that allows artists to show their work direct to the public; his new gallery in Chelsea, which, when it opens next year, he hopes will erase unhappy memories of his time at County Hall; and his life as an art collector.

I ask if the website, which displays works by 10,000-plus artists from around the world, was his idea. "Is it that bad?" he asks. "Is that what you're saying?" I'm not - but he seems to be joking, and goes on to explain that he set it up because "like any religious convert I have discovered the internet terribly late. The more interested I got in the site, the more I thought it could be a useful outlet - showcase, whatever - for artists who don't have dealers. Let them deal directly with collectors. Scanning a website to see work by an artist halfway across the world is the lazy way to do it, but probably the only effective way.

"My little dream is that this can develop into an artists' community, where artists can load up their own work, visitors can browse. You don't have to pay a dealer 50% commission. Dealers tend to buy artists that other artists they already show recommend. If you're not in the loop, if you didn't go to the right art school, if you don't know the right people who have the right dealers, it's very hard to break in."

Of course, looking at images online is not how Saatchi became one of the world's great collectors. In the 1990s, instead of downloading images on to his computer, he visited makeshift galleries in empty hairdressing salons and warehouses, and succeeded in unearthing possibly the most thrilling, certainly the most media-friendly, art Britain has ever produced. He bought up a great deal of what he saw and made a generation of artists - Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, Sarah Lucas, the Chapman brothers, Marc Quinn - rich and famous.

"Most of the art that ended up in Sensation [the 1997 touring exhibition of his collection of BritArt] I first saw put on by artists in alternative spaces. They couldn't spend their whole lives waiting for Anthony d'Offay or Leslie Waddington or any of the other big dealers to come around to look."

Saatchi has described himself as "a gorger of the briefly new", and he tells me that even in his 60s he is "just a sad kid who wants to find a new sweetie". He still spends every weekend in remote parts of south and east London hunting for art. "I wander round the most disagreeable, grotty parts of London - I've become very fond of them - to see shows that have literally been put up in an empty shop or yard."

Saatchi's critics, including artists who have benefitted from his patronage, argue that his buying power, his appetite for "the briefly new", has distorted values on the art market; others say that he has brought his ad agency values to the art world. "It is perhaps inevitable," argues art writer Louisa Buck, "that a man who is himself so adept at visual communication should feel an affinity with artists such as Damien Hirst and Sarah Lucas, whose work relies on a similar ability to distil complex ideas into a powerful and accessible messsage." Naturally, Saatchi disagrees: "That's a facile take on what I do."

It was while Saatchi was working in advertising that he began to establish himself in the international art market, bankrolling his collection from his booming ad agency. He bought his first picture on a trip to Paris with his first wife, Doris Lockhart, an American- born art writer, in 1973. It was a depiction of suburban houses by British artist David Hepher, but Saatchi's taste evolved and he built up a world-class collection of mostly American contemporary art. "There was absolutely no interest here at all. So I spent most of my time going to America - and I was also very interested in Japanese and German art."

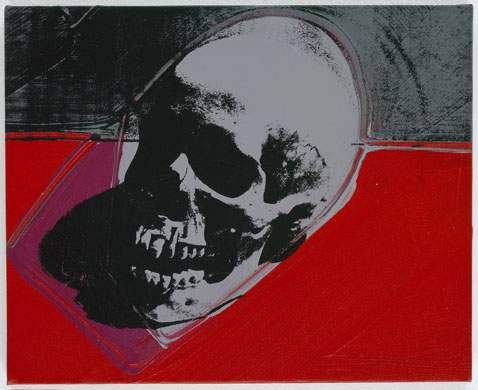

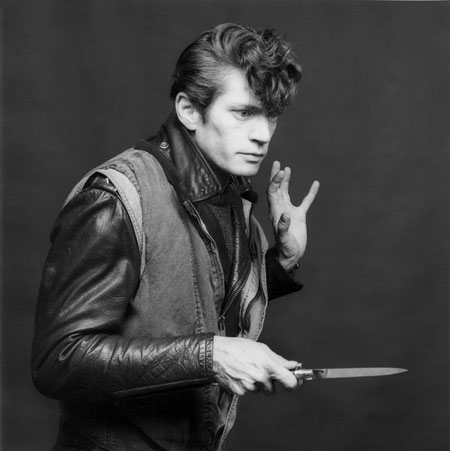

In 1985, he opened a gallery in St John's Wood and started exhibiting his collection in a bid to improve the nation's "unhealthy" attitude to contemporary art. At his prototypical white cube in the suburbs, Saatchi staged the first wholesale shows in Britain of artists such as Andy Warhol, Sol LeWitt, Bruce Naumann, Richard Serra and Jeff Koons.

In the 1990s, Saatchi started offloading a lot of his collection of postwar American art and buying contemporary British art. The first work was Damien Hirst's A Thousand Years, a glass vitrine containing a cow's rotting head, along with maggots and flies. He also bought Tracey Emin's Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995, an embroidered tent that he picked up for £150,000. He paid £13,000 for Marc Quinn's Self, a cast of the artist's head in nine pints of his own frozen blood. Later, there were lovely rumours that builders, hired to refit Saatchi's kitchen after his marriage to Nigella, accidentally melted Quinn's work by unplugging its electric supply. Unfortunately, they weren't true: he sold Self to an American collector in 2005 for £1.5m.

Selling the Quinn at a massive profit is typical Saatchi. He would argue that by offloading it and other works from his collection he has enabled himself to buy new art, thus encouraging new artists and keeping his collection as fresh as frozen blood.

Some artists would disagree, or at least fail to see that Saatchi acts in anyone's interest other than his own. The painter Peter Blake has argued that "he has become a malign influence by building up some artists and leaving others as victims". Blake's implicit point is that Saatchi will buy up an artist's works wholesale and then dump them, thereby ruining a career. There was even a theory that Saatchi had contracted with an arsonist to burn the Momart warehouse in 2004, a fire that destroyed much of his collection - the ultimate, cynical dumping of art that some said was past its sell-by date. "It wasn't terrifically amusing the first time people came up with this," he told the Art Newspaper when this was put to him by a reader. "Now it's the 100th time."

But what does he think of Blake's criticism? "I never did buy a Peter Blake," he says wryly, offering me a puppyish glance. But Blake is hardly Saatchi's only critic. Damien Hirst turned on his patron a few years ago, witheringly describing Saatchi as "a shopaholic". It was a criticism that chimed with Kay Hartenstein's (Saatchi's second wife) description of her ex as "a man of crushes: cars, clothes, artists". (She didn't add "wives".)

"Obviously, if you do what I do you are going to end up making people sometimes happy and sometimes unhappy," Saatchi says. "I cannot, nor would I want to, buy everything I see, so I have to make decisions about what I like. I like to keep my collecting fresh, and I think people have got the message."

Why does he collect? "I like to show off. I always buy art with the idea that I'm going to show it." Interestingly, he thinks his influence over the art world has been clobbered recently by all the hedge-fund billionaires muscling in. "Before, I was always mouthing off about how there aren't enough collectors. Now there are just too many. They're all very young and very rich, and they all like to collect art the way they buy their funds.

"I met one the other day, an American guy who was so young, and somebody told me he had made $500m last year - $500m cold for himself! I wanted to kill him. And he said to me, 'Yeah, well I've got 212 Kippenbergers.' I said, 'Ooh.' Now I know a little about Kippenberger. And I know where all the good ones are. He was very prolific, but he made 60 or 70 really good pieces. He made things every single day, he was one of the artists who had to, but most of it was so-so. So this guy's got 212!

"So we end up laughing at him, and think this is not a real collector. But he's going to wind up looking like the smart one in financial terms, because he's taken the hedge-fund attitude. Kippenberger is going to be big. This guy's got his own art adviser. They all have their own art advisers - ladies dressed in black from head to toe, very chic, very, very thin - and they will have told him about the latest hip artist. So whatever his motivation, he will, in four or five years' time, have made a fortune on Kippenberger. And we will think, 'Why didn't we do that?'"

Because he's not in it for the money? "No, of course I'm not in it for the money. I make a lot of money from the stuff I sell, but then I pay incredibly high prices for the things I want. That's how I get what I like. The market is so insane. What I do when I collect is one of two things: I buy very new people, then I can do what I like. Or, if it's somebody where I haven't got there first - which is the majority of cases because I don't travel - I make a list of my favourite works by that artist and I will try to get those pieces. And if that means I pay 10 times the market price, I don't mind doing it. The important thing is getting the pieces that are going to make the best show. So in that sense, it's best not to think about money."

Does the way he collects distort the market? "I am a strange distortion," he giggles. "I think it comes from a desire to show the artist at their best. Some people are reluctant to let them go unless you pay them a very, very high premium. So I do. That's how you get them."

He says he can't even ballpark his personal fortune. "I've got no idea. I think it's fair to say I don't ever think about money, so obviously in that sense I'm fantastically rich. I'm only rich in that I'm better off than most people. I don't feature on rich lists or anything."

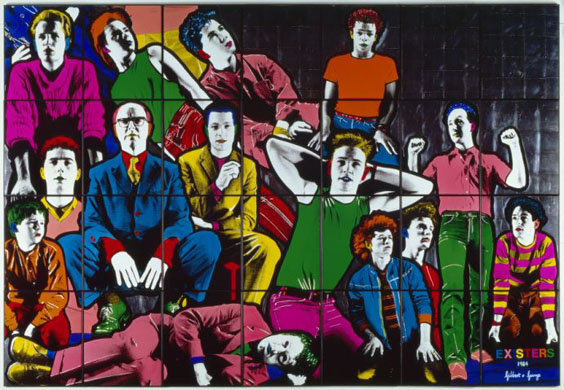

Since the late 1990s Saatchi's problem has not been buying art, but knowing what art to buy. Like many people, he has struggled to identify the YBAs' successors. In 1998, Saatchi announced the coming of a new generation of British artists he called the New Neurotic Realists. Among the "NewNus" (the acronym didn't catch on) brought together for two shows at Saatchi's north London gallery were Ron Mueck, Cecily Brown (whose painting Puce Moment was described by one critic as "an aggressive explosion of sex organs"), and David Falconer, whose Vermin Death Stack was a 10ft pile of dead mice made of cast resin. But was it a genuine movement, or just the former ad man's handle?

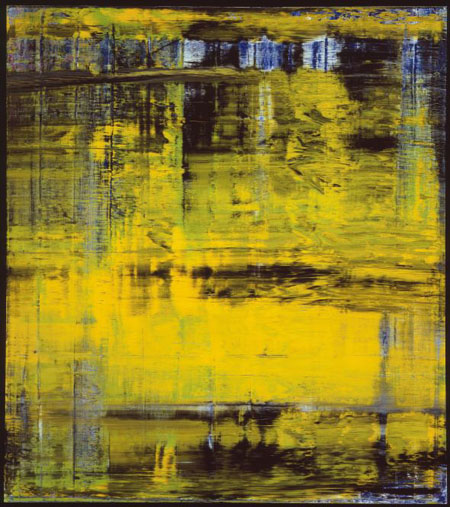

More recently Saatchi announced the return of painting, but his two County Hall exhibitions, the Triumph of Painting parts one and two, suffered a critical mauling. In the London Evening Standard, Brian Sewell wrote that the theme was welcome, but it was a pity that he had chosen the wrong artists. The Observer's Laura Cumming, more devastatingly, suggested that Saatchi was now following taste rather than trying to form it.

The stars of the British art scene, he admits, are less obvious than they were 10 years ago. "I haven't walked into a space and seen a glass vitrine emitting a very foul smell with a dead cow rotting and flies buzzing. I haven't seen anything like that for a long, long time. The era of Damien, the Chapmans and Sarah Lucas has had its golden age. Although those artists are still doing really good art, the next generation - as all generations do - go for a completely different look and take."

He says he sees no coherence in today's artists. Perhaps, I suggest, this was as true of the YBAs: he gave those artists a coherence by buying them up. "That really isn't true. I think that something conspired to make British art suddenly probably the most exciting in the world. I think the art schools were particularly strong at that period, and a group of young artists were particularly strong at that point.

"For the last five or six years the art schools have been very weak, and I see much less good art coming out of England. That's not to say that there isn't good art coming out, it's just less thrilling." What's changed? "Budgets have been slashed and more emphasis is placed on getting paying students. When Michael Craig-Martin was there [as professor at Goldsmiths College in London], they had about four really good teachers. It makes an incredible difference. I speak to many artists who teach there, and they say their audience is there because they think it's a nice, easy gig. They're not interested, they don't see the shows, they couldn't name more than 10 artists."

Even so, Saatchi continues to visit the art schools and tiny galleries in south and east London. "I used to buy lots, but in the past five years I haven't. This year I've bought one artist out of Goldsmiths, nothing from Chelsea. It's not for want of trying."

Instead, he has been buying on the other side of the Atlantic. In October, recent fire damage permitting, the Royal Academy will mount an exhibition called USA Today, which will consist of the best of his recent purchases of American art. "America has been in the doldrums for 15 years, and for me is now as exciting as Britain was in the early 90s." Why? "I have no idea. Probably because there's been a lull, and I think after all lulls the reverse happens."

The USA Today show will feature Dana Schutz, Josephine Meckseper and Barnaby Furnas - none of them familiar names in this country. "If you were to scratch your average very hip dealer in New York, they would know half the names, and another dealer would know the other half," Saatchi says. "Over here, they're completely unknown." Will it cause a sensation, like his last Academy show? "It won't scandalise the Daily Mail. I guess I could tell [Mail editor] Paul Dacre it has a willy or two in it. That would get a headline, wouldn't it?"

If USA Today sounds like just the kind of crowd-pleasing contemporary show you would expect Saatchi to open his new Chelsea gallery with, that's because it is supposed to be. "It's a sensational building, and I've been going potty to try and get in there quickly," he says. But "the builders approached me about a month ago and said, 'Really good news. There's no asbestos. You'll be in by June [2007]. I said, 'Excuse me, but on my [web]site I'm saying early 2007.' They said, 'No, June, and if you want to see why, come round.' So I went round. And it's a huge building site."

In 2003, when part of the former GLC building on London's South Bank came up for grabs, Saatchi swooped. "It had immense foot traffic outside," he says. "It's just like Oxford Street on a Saturday afternoon. So our numbers were really good." But many critics didn't like the new gallery, and the public balked at the £8 charge, particularly when Tate Modern's permanent collection, just a short stroll away, was free. "The art world was tuned to the idea that art galleries were big white spaces," says Saatchi. "So when they saw wood-pannelled corridors and rooms it didn't suit the art world's perception."

That perception was hardly Saatchi's biggest problem. "We had an incredibly hostile relationship with the landlord. Everybody who worked there was utterly miserable, morale was terrible and I was spending my whole time with lawyers, which I really don't like doing, to no avail."

Does he have any happy memories? "My best memories of County Hall are that we were very popular with schools. We must have had 1,200 to 1,300 schools come. I know I sound like some ghastly creep, but there is something enchanting about seeing groups of children sitting round a Chapman brothers piece with penises coming out of girls' eyes, drawing it very neatly to take back to their teachers."

At one point during those dismal years, Saatchi thought of offering his £200m collection to the Tate. "I thought, 'Wouldn't it be much easier to give the headache of showing my collection to someone else?'" That was when he phoned his old chum Nick Serota and started up one of the great British art world rows.

"I rang up Nick and said, 'Remember when we first walked around the new Tate and you said we have the opportunity to extend it another 50%? Well I'm miserable here, I'm thinking of leaving all my stuff to the Tate.' He said, 'Those spaces are already committed.' I said, 'Oh,' and that was the end of the conversation."

Of course, this wasn't how the story was reported. Instead, Serota's refusal was seen as the latest round in a long-running feud between the two most powerful men in the British art world. Saatchi had reportedly criticised the Tate-run Turner Prize. The London Evening Standard claimed that, in 1997, the Tate approached Saatchi about acquiring work to mark Tate Modern's opening, and that the following year he offered Serota 86 works by 57 British artists - including Langland and Bell, Turner prize-winner Martin Creed, and Glenn Brown - none of which were accepted. Saatchi denies that the abrupt phone call to Serota was the latest instalment of a row fuelled by mutual loathing.

"I'm mad about Nick. Genuinely, I think he's a sensational man. So the last thing I want to do is create some friction between us. But it obviously turned into a story." Saatchi is now pleased, at least publicly, that Serota didn't accept his offer. "I think it would have been a great shame - I can do things Nick can't. I think London does need to have somewhere where very new art can be showcased."

Doesn't that leave the Tate's collection of British contemporary art looking pretty weak? "The Tate's got a lot of good stuff." That said, he is hardly a cheerleader. "I'm never going to be happy with any museum's collection because they all get their stuff in mysterious ways. They rely on gifts, which can often be of second or third rate quality, or they wait so long to get behind an artist that all the best works have ended up with people like me."

Saatchi says he has taken a self-denying ordinance to buy nothing from his Your Gallery website for six months. "I didn't want there to be any confusion about what the site was there for. I wasn't intending the site to be used for artists to present their work to any one individual. So I thought I won't stick my oar in until it has a life of its own. I've made a note of all the artists on there that I think are very good - it's a surprisingly long list."

He says he will probably launch his new gallery with an exhibition of Chinese art. "I've always been very sneery about Chinese art because it looks terribly kitsch, and a lot of it looks very derivative. But there's enough stuff to put on a good show. So far I've found six artists who I think are good on any stage. My rule is: if you can put this in the Whitney Biennial and nobody is going to say, 'Oh that's very good for a Chinese artist,' then that will be fine."

He didn't visit China to find his artists. "I don't travel. I'm very, very, very lazy. I'm going to be like one of those people who get fatter and fatter and become one with the chair, and they're found years later." Later in 2007, he plans to stage the third in his series the Triumph of Painting, as well as what remains of his BritArt collection.

It is unusual for someone to retain such enthusiasm for new art, I suggest. "Barking mad, I think is what you're trying to say. It is true, I worry about my sanity. I still take a childish pleasure in doing the same things I have been doing for a very long time. Artists are always producing new, interesting things. I don't believe this argument that everything's been done. Artists break the rules all the time. Artists make art that doesn't look like art. Nobody could foresee that someone could make art out of a cow's head and flies, a sheep in a tank of formaldehyde, or a row of girls in brand-new Nikes with penises coming out of their heads. Nobody could foresee that this was the direction art was going to take and that it would be great art."

But Charles Saatchi possessed two things nearly as rare as that foresight: the wit to realise, 16 years ago, that something extraordinary was happening in the British art world, and the savvy to buy it up fast. He got the jump on the art market once. Has he the wit to do it again? Will his exhibitions of new American and Chinese art show that Saatchi has still got it, and can flaunt it to the despair of rival collectors, disaffected artists and press critics? It seems unlikely that there is a new Damien, Jake, Dinos, Tracey or Sarah awaiting those who are keen to see what Charles bought next. Unlikely, but not impossible. Over the next few months, we will find out for sure.

· USA Today starts at the Royal Academy, London W1, on October 6. The new Saatchi Gallery is due to open next June. Your Gallery is at Saatchi-gallery.co.uk/yourgallery